According to General John J. Pershing’s autobiography of World War I, he and the top officials of the American Expeditionary Forces were worried about maintaining the morale of their army at a high level. To address this, he delegated the task of creating a publication to Colonel Dennis E. Nolan and Lt. Colonel Frederick Palmer, who then appointed Second Lieutenant Guy T. Viskniskki of the 79th Infantry Division to lead the project.

It appears that Lieutenant Viskniskki, who was working with Lieutenant Colonel Palmer at that time, had expressed significant backing for the creation of the publication. As a veteran of the Spanish-American War, he was familiar with the newspaper industry, having served as an executive for a newspaper syndicate before joining the A.E.F.

In the February 7, 1919 issue, Captain Viskniskki, now in his new rank, mentions that he took the initiative to propose the name “The Stars and Stripes” for the publication. He also outlined its objectives and policies, organized it, and served as the officer in charge until several weeks after the armistice.

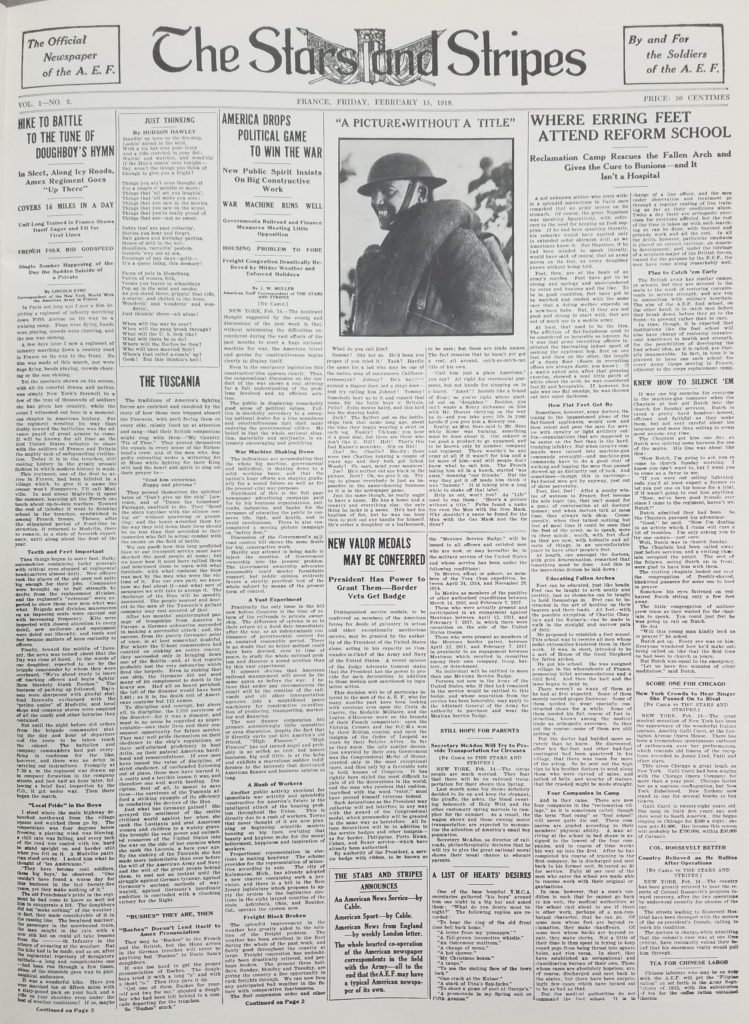

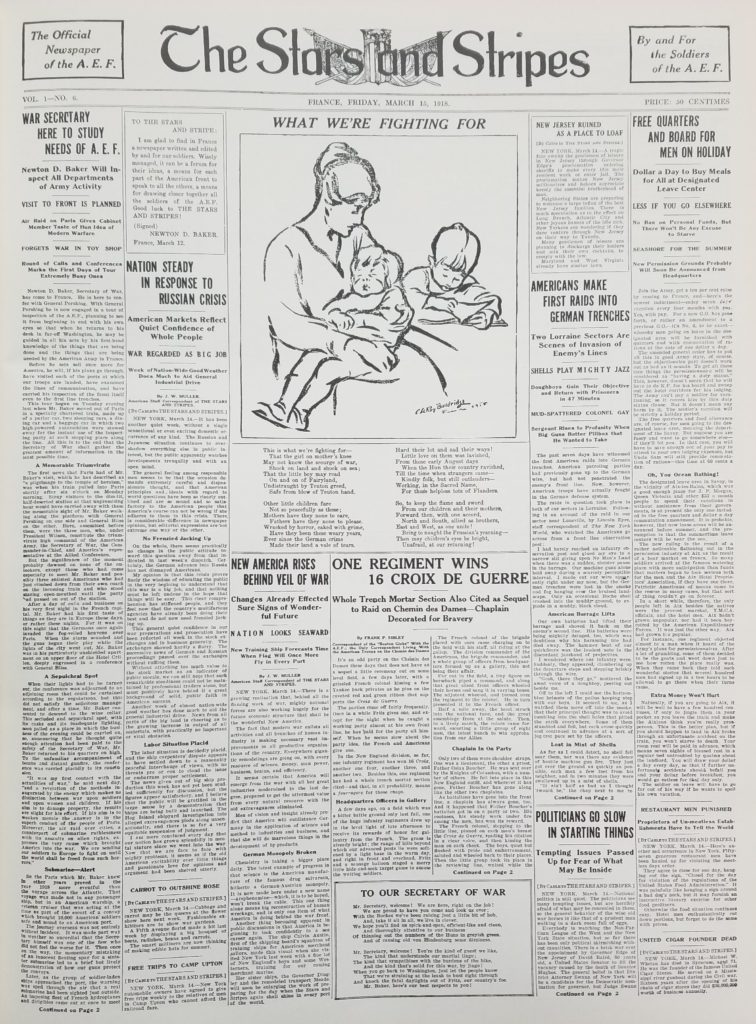

On February 8, 1918, the day of its first publication, Bulletin No. 10 was sent by General Headquarters of the A.E.F. to all relevant commanders. This bulletin provided general details about the newspaper, stating that it would provide the latest news and sports updates from home via cable. It also informed commanders that their units would not only be able to read about their own activities but also other units and their endeavors.

Furthermore, the newspaper would also serve as a platform for publishing poems, stories, articles, caricatures, and cartoons created by members of the A.E.F. The closing paragraph emphasized the hope that all organization commanders would provide their wholehearted and timely cooperation to the newly established Stars and Stripes. This bulletin was issued under the authority of General Pershing.

According to a roster included in the last edition of June 13, 1919, a total of six men were on duty during the first publication. The final edition also revealed that 1,000 copies of the initial edition were printed and sold. Despite this modest start, the newspaper grew in popularity, and at its peak, it reached a circulation of 526,000 copies. The roster also listed approximately 350 soldiers who served with the newspaper throughout its 71 issues.

To what extent was the newspaper created by World War I soldiers deemed successful?

In the renowned weekly publication of World War II, Yank Magazine, Cpl. Burtt Evans, a member of their staff, described the World War I newspaper as “the wildest, most vibrant, highly cherished, and incredibly successful newspaper ever published.” He credited it as the precursor to both Yank and the World War II Stars and Stripes. This would suggest that the Civil War editions served as the predecessors to these later issues of World War II. (See Yank February 10, 1943 issue, pages 4-5.)

On pages 8-9 of The Pacific Stars and Stripes dated February 8, 1953, Andrew Headland Jr., a member of their staff during the Korean War, expresses, “While there have been newspapers that were better edited, larger in size, more influential, and more impressive than the 8-page full-size weekly Stars and Stripes, few publications can rival its eloquent style, captivating content, and the respect it commanded for its principles. The short-lived yet glorious Stars and Stripes of World War I left an indelible mark.”

Which Army and Marine soldiers, alongside Lt. Viskniskki, contributed to the success of this newspaper and fulfilled the morale-boosting expectations of the Iron commander?

The man who would eventually replace Lt. Viskniskki after he was promoted up and out as editor was a sometimes cantankerous, but brilliant Pvt. Harold W. Ross is a 26-year-old, well-traveled news reporter. After the war, he moved to New York City and became the founder of The New Yorker Magazine.

Sgt. Alexander Woollcott, a 31-year-old dramatic critic for The New York Times, became the chief correspondent. Due to his poor eyesight and unconcern for danger, another reporter usually accompanied him as he boldly patrolled the front-line trenches. After the war, he returned to New York City and became extremely popular as a journalist, critic, writer, actor and radio broadcaster.

Pvt. John T. Winterich, a 27-year-old former reporter and copyreader for The Springfield Republican (MA) was considered the most reliable and knowledgeable member of the staff. When Lt. Viskniskki left The Stars and Stripes, the staff was given the responsibility of choosing their new editor. Winterich was nominated by Ross for the position. However, the shy Winterich declined. The staff then chose Ross to be their editor. After the war, Winterich succeeded Ross as editor of The American Legion Magazine.

Hudson Hawley, a former newspaper writer with The Hartford Times (CT) and The New York Sun, was credited with writing the copy for the first two issues of The Stars and Stripes. We presume he was the top writer for the Stripes since we can not find a record of his being a correspondent with Woollcott, Ross, and Winterich.

Abian A. Wallgren, a Marine private of the 5th Regiment, hailed from the Philadelphia, PA area and his extremely popular cartoons appeared in all 71 issues of The Stars and Stripes.

Pvt. C. LeRoy Baldridge was probably the only unattached infantry private in the A.E.F. The reason, he was a commercial artist in the Chicago area (home address given 2400 A. St., San Diego, CA) who left for France shortly after the war broke out in 1914. He joined the French Army as a truck driver and remained so until June 1, 1918, when he transferred to the American Army and The Stars and Stripes as a private. His serious cartoons were well respected and could draw immediate attention to a cause.

Franklin P. Adams, a 37-year-old Army intelligence service captain was already a well-known syndicated columnist in the United States. His new column in The Stars and Stripes, “The Listening Post” was filled with his wit and poetry. In the years following the war, his popularity grew with his column, “The Conning Tower.” In 1938, he became even better known as one of the experts on the radio show “Information Please.” In Mr. Headland’s Stars and Stripes article in 1953, he mentions that “Until recently Cpl. Timothy Adams, son of the famed Franklin, was a reporter in Korea for The Pacific Stars and Stripes.”

Grantland Rice, a 38-year-old 1st Lt., and accomplished sportswriter, left his job and family in New York to become an artilleryman with the 30th National Guard Infantry Division from his native state of Tennessee. When his outfit, the 115th Field Artillery Regiment, arrived in France in the spring of 1918, he was surprised by orders to report to Paris and The Stars and Stripes. Of all the soldiers who worked for the newspaper, Granny Rice seemed to be the one who wanted to stay with his regiment. After four months of service, which included covering the battle at St. Mihiel with Ross and Woollcott, he reported back to his regiment. Even then he sent stories and poetry back to the Stripes. After the war, he returned to the New York Tribune and had a great career during the Golden Twenties.

Two officers in charge should be mentioned in connection with the newspaper. Major Mark S. Watson of The Chicago Tribune replaced Viskniskki as officer in charge on November 29, 1918. In 1945, he won the Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting while with the Baltimore Sun: the second officer, Capt. Stephen T. Early of Crozet, VA, served as the assistant officer in charge and World War II as the press secretary for President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

During the existence of the World War I Stars and Stripes, the ancient art of poetry was extremely popular with the doughboys. They, in fact, contributed most of the poetry with few exceptions. One exception is well worth mentioning. Rudyard Kipling, whose respect for the soldier was well known from previous publications, allowed his verse, “Justice” to be first printed in the November 1, 1918 issue of The Stars and Stripes. Shortly after this poem appeared his only son, John was killed in action while serving with the Irish Guard.

Sometime prior to the Friday, August 16, 1918 issue, correspondent Alex Woollcott brought back from the front lines of the famous 42nd Rainbow Division a copy of verse to be added to “The Army’s Poets” section of the Paper. This poem had been written after a German shell scored a direct hit on a dugout occupied by the Americans. Nineteen young men from the 165th Infantry Regiment were buried alive on the spot—a member of this regiment and one of America’s most famous poets, Sgt. Joyce Kilmer wrote, “The Woods Called Rouge-Bouquet” in their memory. Kilmer and Woollcott were acquainted from having worked simultaneously at The New York Times. Sgt. Kilmer, best known for his poem “Trees,” died a few weeks later on July 30, 1918, while fighting near the Ourcq River.

The Stars and Stripes lost members during the war, although none were direct battle casualties. Four of the men died of sickness as a result of service to the newspaper. They were Pvt. Carl D. McIntosh of Los Angeles, CA; Sgt. David R. Bawden of Detroit, MI; Sgt. Homer G. Roland of Des Moines, IA and 1st Lt. William F. Miltenberger of New York City, NY.

The final issue of the World War I Stars and Stripes has a long article entitled, “Stars and Stripes is Hauled Down with This Issue.” It is an interesting article full of history, names, dates, facts, figures, and, of course, Stars and Stripes humor. In the closing paragraph, they thanked Gen. Pershing and the A.E.F. staff for their support. Finally, they mention a memorandum that came down from headquarters, probably from Pershing in regard to whether or not the paper was to be run for the enlisted man. “And it said in substance: The style and policy of The Stars and Stripes is not to be interfered with. It never was, and thus, the old sheet was able to achieve whatever measure of usefulness, whatever place in hearts of its fellow Yanks it may be credited with, now or in times to come.”

That “times to come” would be Saturday, April 18, 1942, in London. The Stars and Stripes was welcomed back into print by one of its World War I doughboys, General George C. Marshall.